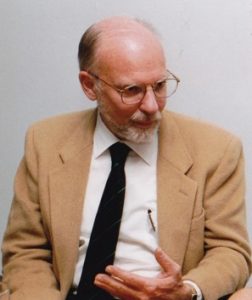

Bruce Bridgeman

1944-2016

Bruce Bridgeman was tragically killed in an accident on July 10, 2016 while in Taipei.

Bruce was a UC Santa Cruz professor of psychology and psychobiology and an internationally renowned researcher on spatial orientation and neuroscience.

Bridgeman joined UC Santa Cruz in 1973 and remained with UCSC throughout his career. Though an emeriti professor, Bridgeman was reappointed to teach courses in neuroscience and evolutionary psychology, the subject of one of his textbooks, and had several active experiments running in his lab at the time of his death. “Bruce remained a vital member of the psychology department,” said professor and department chair Campbell Leaper. “He maintained a very productive research program that included several UCSC students as research assistants.” Read full article...

Bruce Bridgeman Tribute (Part 1)

Bruce Bridgeman Tribute (Part 2)

The Bruce and Diane Bridgeman Fund

To honor Bruce Bridgeman, the Professor Bruce Bridgeman, Ph.D. and Diane Bridgeman, Ph.D. fund has been established to assist UC Santa Cruz graduate students in cognitive psychology who would not otherwise be able to fully afford the cost of their studies.

It is created by his family, Diane Bridgeman, Ph.D., Natalie Bridgeman Fields, J.D. and Tess Bridgeman, D. Phil., J.D.

To donate click HERE.

Career

Presentation on Bruce’s Career

as delivered at the 2016 APA conference

Memories

If you would like to contribute a memory to this site, please send your post to:

psycdept@ucsc.edu

Vivien Chung

I stumbled upon the sad news of Professor Bridgeman’s sudden death recently. I attended school with his daughter Tess from first grade through High School. I can still fondly remember the presentations he and his wife gave to our 5th grade class (maybe younger). One was discussing the importance of reversing the greenhouse effect, and other on the education of women around the world in order to reduce over population. These were very serious and timely issues, and Bruce and Diane spoke in such a way as to make me feel I could make a difference. The time they took to speak to us really affected me and helped influence my world view. My heart goes out to his family and friends who must miss him dearly.

Brian Fisher

Anthony Adams

Dear family and friends,

I am unable to attend the tribute tomorrow (Saturday), but I do want the family to know that so many of Bruce’s UCB friends, including me, absolutely treasured his curiosity and open-mindedness as he explored vision– and science in general.

A superb colleague.

We will definitely miss him, and remember him.

Joe Palca

I met Bruce in the fall of 1977 when I started grad school at UCSC. I’d come to Santa Cruz to work with Ralph Berger, a sleep researcher I’d admired. The human sleep lab was in the basement of Kerr Hall, right next door to Bruce’s lab.

Prior to grad school, I had worked as a lab technician in a research institute. I learned that some researchers were not at all generous when it came to sharing resources or ideas with their neighbors. Bruce was the opposite. Always helpful, always generous with his time and his equipment. He epitomized the way science should work.

In winter quarter of my first year, I was a TA in Bruce’s course on physiological psychology. I loved that class, and I loved being Bruce’s TA. Even though he was a lofty professor and I a lowly grad student, he treated me like an equal. At one point in his class, we covered the topic of the function of micro-saccades. These are tiny eye movements that occur all the time, but nobody knew what they were for. One explanation was that they might be providing slightly different perspectives on a visual scene that might help the brain construct a more detailed scene when we need to do very precise tasks like thread a needle. I liked this explanation, but there was a problem with it. If it were right, the number of micro-saccades should go up as a subject performed the task of threading a needle…but a group of researchers had tested this, and they found the number went down, not up.

I wasn’t quite ready to give up on this hypothesis, so I told Bruce there might be a flaw in this group’s methodology. Maybe the physical act of threading the needle was suppressing all other muscular activity, including the tiny eye movements. If the subjects had merely been asked to watch a thread heading for a needle and decide if would go through the eye or not … without having to actually manipulate the thread themselves…. maybe the number of micro-saccades would go up.

To my total surprise, Bruce said, “let’s do the experiment.” So here I was, a first year grad student collaborating on a scientific paper. Bruce even offered to make me first author. I was impressed then, but even more impressed subsequently as I learned that not every mentor was as generous with his time as Bruce was, or as willing to share credit.

By the way, my idea was wrong. The number of micro-saccades still went down even though our subjects didn’t have to do anything but sit there and watch. But the paper made it into a top tier journal, and it still gets cited.

In the years since 1982 when I graduated, Bruce and I kept in touch. I was pleased that he embraced my decision to leave academic science, another quality that sets Bruce apart from many other mentors.

I feel privileged to be counted among the people he called friends. I’ll miss him a lot.

Alan Venable

I was disappointed that Bruce’s memorial was scheduled for a day when Gail and I were already committed to travel in Europe.

Bruce and I grew up together in Pittsburgh PA from around 1953, when we both must have been about eight or nine. That was his family moved to Maryland Street, near Third Presbyterian Church, where I think Elsie was working as a secretary, and where my father, Emerson Venable, a socialist-minded Unitarian chemist, was Cubmaster and later Scoutmaster of Scout troop 76.

Bruce joined me in the Cubs and at K-through 8 Liberty School in Shadyside. Like my mother, Elsie became a Den Mother. From then on, Bruce and I were friends and friendly rivals until we finished at Peabody High.

My parents immediately liked Bruce and Brent and deeply admired Elsie–a dedicated single mother who, like they, also took on community work. I always liked Elsie, too, and I enjoyed the free-wheeling atmosphere at their birthday parties and times when I’d stop by after school.

I think Bruce and I felt more compatible with each other than we did with other lower-to-middle-class agemates in grade school. In addition to academic purpose, we also shared-was a family-nurtured sense of the practical–as opposed to the fashionable–and a general attitude of goodwill toward and respect for other people.

And as much as I was tempted sometimes to offer to trade my own annoying little brother Tom for Brent–I don’t think Bruce would have taken the deal. Well, at least not even-Steven.

Academically, Bruce and I must have pushed each other in grade school, though neither of us was much driven by competition. We were two fairly straight-arrow, straight-and-narrow boys, brought up to value teamwork.

One after-school project we shared around eighth grade must have been inspired by the Sputnik craze and the sudden demand that everybody study physics. It was a club, “The Society of Birdbrains” that also included our egghead classmate Bobby Bornholz, in addition to Brent.

Beyond gathering to sing our theme song– “Up in the Air Junior Birdman” — our mission was to build a rocket. Mainly Bruce and I, as I remember, did the actual building, in my father’s basement workshop, adjoining his basement chemistry labs. From an old tin can, we cut out and soldered fins and a nose-cone onto an empty 8-ounce Donald Duck Concentrated Orange Juice can. As propellant, I think we settled on the solid jet fuel pellets one could buy at a hobby shop to power the little Jetex, jet-model-airplane engine I happened to have at the time. We had the fuse, as well. We were the practical side of the club. But being somewhat safety minded, we never quite got around to the launch.

In eighth grade we took evening dance lessons at the Unitarian Church, at which we were about suave (or not) and pursued the same handful of girls, with parallel disastrous results, I’m sure.

In all, we were Cub, Boy, and Explorer Scouts together through the end of high school. The height of our partnership in Scouts was the summer after 8th grade when, at my father’s suggestion, Bruce and I carried out a five- or six-day cross-country trek by ourselves from Pittsburgh south to West Virginia and the copperhead-infested Cheat River wilderness camp.

Each morning on topographical maps, we’d plot our hill-heavy course along trails and farm roads, then usually get lost somehow pretty early on, and stop, ideally, at a country store to lunch on powdered-sugar doughnuts and a quart of milk apiece. Then hike until dusk to camp and cook and sleep under the stars, just out of view of the road, if any.

Actually, after nearly a week of Bruce’s company along with my own, my nerves were pretty frayed by the night we reached Cheat Lake, the rain coming down in buckets, and crammed ourselves under a picnic bench for a wet and sleepless night.

Maybe five or six days together, just the two of us was asking a bit too much of thirteen-year-old. Or maybe I just became too aware that Bruce was stronger physically and had better sense than I, and was, well, more practical after all.

Later that summer we led a few other Scouts from our troop on a very hilly four-day back-road bicycle trip up north about 80 miles to a Camp on Lake Tionesta–up near Cook Forest. Through our teen years as Explorer Scouts we also, canoed the length of the Allegheny River, attended national Scout jamborees in Valley Forge and Colorado Springs, and trekked with burros about ten days in New Mexico, in the mountains of Philmont Scout Reservation. In all these experiences, when we needed to be able depend on someone, I think we turned first to each other.

As Western Pennsylvania teenage Explorers we also went spelunking–co-ed and otherwise–on weekends down in numerous caves; held dances with Senior Girl Scout groups, including some very exotically Catholic girls, and volunteered for co-ed work-weekends, to ready nearby Girl Scout camps for the summer camping season and to closing them down in the fall.

Around the start of high school, Elsie and the boys moved to the Highland Park neighborhood, probably to be nearer the settlement house that she administered for much of her career. Shadyside and Highland Park both fed into Peabody High, where students were shunted onto business, secretarial, industrial, and college-bound tracks. Bruce and I took the same four years of math and other accelerated academics. I studied French, he German in line with his interest in science.

In high school I went out for track. Though Bruce and I had fulfilled our Scout Lifeguard credentials together one summer at Camp Guyasuta, I was amazed when he joined the Peabody swim team. Amazed because the swimming coach was the dreaded “Wild Bill Evans,” –who’d spit tobacco juice at a drain, then swing his hawk eyes around and snarl, “Hell’s bells, boy, I said MOVE your ass!” He drove his swimmers proudly, mercilessly to the city title every year. I don’t think Bruce stood out on the team. I’m not sure how long he kept it up. But I was impressed.

Both of us sang in the Peabody senior choir and went on with music throughout our lives. Bruce and I also took part in a small Pittsburgh community of left-leaning, intellectual youth that I spent all the time I could with toward the end of high school: young leftist peacenik spawn of Jews, Unitarians, Quakers, and labor lawyers, with a sprinkling of radical Catholics, re-unredeemed Presbyterians, and Red-Diaper babies. Like me he was in and out of free-form Friday-night gatherings for singing and talk about peace, prejudice, bombs, kibbutzes, and the evils of capitalism. Many years later, one of our last long conversations was about shared interests in evolutionary science as a basis for present and future morality.

My parents were Cornell alumni. After corralling my two older brothers to go there, they also persuaded Bruce to apply, and wholeheartedly supported his admission and scholarship applications. They were proud and pleased to see head out into the world and achieve so much in his career.

Two last qualities of Bruce I’d like to mention. The first was pointed out to me by John Burchfield after our 60th high school reunion. John called it “an almost childish enthusiasm” that Bruce still showed for the joy of discovery through careful research.

The second was Bruce’s lifelong honesty–his openness to re-considering old conclusions in the interest of moving closer to truth. For me, he set a standard for consciously re-examining old overly comfortable ideas, in the light of new evidence and reason.

I hope this gives some sense of the richness of the childhood that Bruce and I shared, and why I continued to admire and respect him over the years.

Lacey Okonski

I felt a great sense of sadness when I learned of Bruce Bridgeman’s passing. Bruce was the type of intellectual who could put aside theoretical differences, as was often the case for us, and still give his full consideration to support your research or work. He had an incredible mind as was evidenced by the sheer amount of content he presented in his behavioral neuroscience class. Beyond his academic greatness, Bruce was also very kind with an amazing sense of humor. I will always remember him fondly whizzing by me on his bicycle with incredible speed (and chuckling after he would successfully startle me), making South Park jokes at colloquium, casually hanging out in his lab talking about language research, and celebrating the end of the year with Martinelli’s sparkling cider at the Bridgeman home with Sabine and other labmates. When Bob Bjork came to visit the campus and review our department I remember recounting to him how welcoming the professors at UCSC can be and in particular telling him of how earlier in the day Bruce helped me find some references in his office and even let me borrow a text on the subject marking the relevant pages. Just before Bruce passed, we had a very fun conversation on Phil Tseng’s facebook thread where ultimately we all joked that Bruce was a Cognitive Lord and I confirmed that this was the case. I am so glad we got to have this one last joke together and that I was able to pay that one last tribute to a man who I respect so much. His memorial falls on my birthday but I wouldn’t miss it for the world. Rest in Peace Bruce!

Kathy Miller

Bruce’s untimely death leaves a hole in all of our lives. It also leaves an empty space in his driveway where he played with his grandkids. He absolutely radiated with joy and pride when he was with them.

Wolfgang Prinz – Leipzig, Germany

I have longstanding good memories of meeting Bruce and collaborating with him – first in a study year at the Center of Interdisciplinary Studies at the University of Bielefeld in the mid 80s and then, a decade later, at the Max Planck Institute for Psychological Research in Munich where Bruce visited us regularly and served as a Scientific Advisor for the Institute. The last time I saw him was again in Bielefeld at a conference on occasion of the 25th anniversary of our former study year.

What I liked so much about Bruce’s science was the classical style of his approach. As concerns his research agenda, he was very much committed to classical problems of perception and action and the legacy of authorities like Helmholtz, von Holst and Gibson, rather than tackling novel issues in the field that may be easier to solve. As concerns his style of doing science, he was likewise committed to the classical attitude of friendly skepticism – skeptical reflections and discussions of theoretically motivated opinions rather than mere collection of data and empirically substantiated facts.

As I see it, Bruce was, on a worldwide scale, certainly one of the most prominent scholars engaged in the study of relationships between perception and action in the spatial domain. Moreover, he had the talent to practice his science and its in-built skepticism in an extremely friendly and constructive manner so that talking to him was always a pleasurable intellectual experience. I am sure that his memory will be enduring.

A conference at Holzhausen, Bavaria, Germany, August 1996

Discussion at the Max Planck Institute for Psychological Research – Munich, November 1999

Center of Interdisciplinary Research, University of Bielefeld, June 2010

Elizabeth Stark

Bruce did a post-doc with my father at UC Berkeley, when I was very little, and in the years I was growing up, we visited the Bridgemans; I have happy memories of this time. My father was enormously pleased by Bruce’s professional success and his brilliance, as well as by his personal success-his wonderful family. I loved them. I remember playing with—and adoring—Natalie when she was little, remember Tess as a tiny baby, already full of personality and vigor. As we played, our parents talked and laughed in the bright, open living room of the Bridgemans’ house. I remember Bruce’s smile, his calm, solid presence, so complemented by and contented with Diane’s. When I graduated from UCSC, the Bridgemans’ generously hosted my graduation party. I have such a strong, visceral sense of Bruce—how his whole being expressed his good nature and good humor, his alert intelligence conscientiously applied. It’s hard to believe he’s gone.

Trevor Chen

As a prospective graduate student in the spring of 2001, I first met Professor Bruce Bridgeman during my visit to UC Santa Cruz. He kindly gave a presentation on the psychology of vision. During his lab tour, he showed me various fascinating illusions in visual and spatial perception before explaining the underlying principles of these phenomena. Afterwards, he talked to me about graduate school and research. His passion for science was inspiring.

Later that year, upon my arrival for the start of Fall Quarter, I attended an orientation followed by a gathering, during which Bruce sang with students. Others informed me that Professor Bridgeman and Professor Massaro, both renowned experts with decades of academic experience, would together teach my first graduate-level course in cognitive psychology. Awestruck by their accomplishments, I looked-up to them and wanted to become a professor like them. Bruce’s sense of humor helped create a relaxing atmosphere that made me less nervous.

Throughout the years, I enjoyed talking with and learning from Professor Bridgeman. At colloquiums, seminars, classes, and office hours, he often had insightful and interesting comments. At times, he talked about educational policy or social issues. During lunches, he fondly recalled stories about his daughters using toy trucks to play conversation games, going to schools, and becoming lawyers. It was clear that Bruce was a very proud father.

Although Professor Bridgeman was not my advisor, he was willing to help me. For example, when I was examining research on singing behavior, he agreed to sing in the lab for my project. Also, he was on my qualifying-exam committee, offering enlightening comments that improved my work. Moreover, Bruce provided in-depth knowledge on the history of science as well as academic wisdom in regards to the scientific community.

I never did become a professor; since graduating from UC Santa Cruz, I have been teaching high-school students. During my subsequent visits over the years, Professor Bridgeman shared reminiscences and conversations with me about various topics. Last year (in 2015), he was a guest speaker in my summer camp for high-school students. He could debunk myths and instill wonder at the same time. In his lab tour, he showed the same patience and enthusiasm as what I first witnessed back in 2001.

Following his presentation, we went to eat lunch on-campus, just like when I was in graduate school. Then, after Professor Bridgeman left on his bicycle, I took a good look back at the Psychology Department, one that he helped to build through his research, teaching, and service. My last image of Bruce was that of a smiling scientist who took the time to inspire high-school students. But beyond science, he also taught me the value of human kindness, something that could not be learned from any journal article or textbook.